After reading at least a hundred first pages over the past 3 weeks, I’ve got some thoughts on how the writer can catch a reader’s attention. And some ways to make sure they continue to read past the first paragraph.

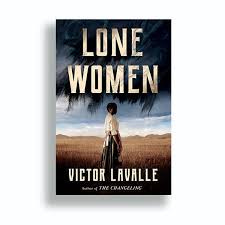

We’ll start this conversation by looking at Lone Women by Victor Lavalle, because this is a book that starts with startling action and doesn’t let up for 275 chillingly sculpted pages. Even if the reader skips the flap copy, they’ll quickly be invited into a scene of intrigue and horror.

There are two kinds of people in this world: those who live with shame, and those who die from it. On Tuesday, Adelaide Henry would’ve called herself the former, but by Wednesday she wasn’t as sure.

The novel starts with a dichotomy, one that will either prove to be true or false by the end. Linking our beginnings to our endings can show emotionally or thematically how far the main character has journeyed through the narrative. These kinds of statements can intrigue the reader, pull them in, get them to ask an initial question. Narrative should be question-generating engines. But we can’t just have the statement; it must be applied to our main character. And this is a very engaging way to introduce our main character and a great way to make sure that they are on the scene as soon as possible! And it’s subtle, but this opening is already hinting that Adelaide Henry has started her transformation. She’s already becoming a different person! We love to emotionally attach to people who are ready for change, who we can experience this change with over the course of the story.

If she was trying to live, then why would she be walking through her family’s farmhouse carrying an Atlas jar of gasoline, pouring that gasoline on the kitchen floor, the dining table, dousing the settee in the den? And after she emptied the first Atlas jar, why go back to the kitchen for the other jar, then climb the stairs to the second floor, listening to the splash of gasoline on every step? Was she planning to live, or trying to die?

I love how the narrator starts to answer the reader’s initial questions, how it is all framed by this opening dichotomy. Though Lavalle uses rhetorical questions, there’s nothing static here. There is very dramatic and possibly tragic, out of the norm, and deviant action here! We may even be appalled, but Adelaide has our attention now! Writers need to find the actions, the moments where their characters act in new ways from their norm, in ways that are unique and specific to them, but that are also fresh, and maybe off-kilter.

There were twenty-seven Black farming families in California’s Lucerne Valley in 1915. Adelaide and her parents had been one of them. After today there would only be twenty-six.

I love the interruption of the rhetorical question here, how the narrator takes back control from us watching Adelaide spill gasoline. Lavalle has twisted these two factual statements, sheared them from the over-wrought emotion of the mini-scene before it, and the emotion, as understated as it is, is chilling. I definitely want to know what happened to her family. I want to know where she will go once the house burns down, and just how responsible is she for whatever has happened to her parents?

Adelaide reached the second-floor landing. She hardly smelled the gasoline anymore. Her hands were covered in fresh wounds, but she felt no pain. There were two bedrooms on the second floor: her bedroom and her parents’.

I love this move back to the scene, back to the sensory details, allowing me to enter back into the experience. The best writers know how to manipulate the use of the narrator, to allow for the necessary context and backstory, while keeping us engaged with the character’s actions. This balance is so difficult in the opening page, because there’s so much we want the reader to know. But we have to find the right timing of when to provide context and when to rely on the sensory experiences of the story. Here, Lavalle is doing an excellent weaving of showing and telling, and withholding and divulging.

First Page Tips:

If you start with a fact, dichotomy, or overarching idea, make sure it’s one that raises questions or can be linked to the ending of the story.

Allow your character to start with action, preferably something outside their normal routine.

Have your opening scene start in a setting that shows the world slightly off-kilter. (Avoid familiar settings like funerals, hospital beds, waking up in their bed, or the breakfast table.)

Balance scene with exposition or context, show how much control the narrator or the point of view has over the telling and filtering of the story on the first page.

Write against the grain of the normal emotional state of the character and/or the moment.

Use sensory details to create a sensory experience.

Show us a character who is ready to change, who will fight for it or against it, so we have someone to root for. (We love to emotionally attach to people who are ready for change.)

Prompt: Consider a two kind of people dichotomy that applies to your main character. How could they go from one side to the other? What event might make them transform from one person to a different person? Where is the best place to start this hint of change? If revising, how can you use your narrator or point of view to show a master of control over withholding and divulging pertinent information? Constantly ask your self do we need to know information and if so, do we need to know it yet? If not, is it leading to reader questions? How can you streamline the reader question-generating engine of your story?

Until my AALA membership is approved, I’ll be taking queries at tommy @ rosecliffliterary.com. My MSWL is here!

Want to pitch me live?

Writing Away Refuge Zoom Pitch Retreat

April 05, 2025 11:50-3:50 Central Time, Zoom

The 2025 Writing Workshop of Chicago

June 21, 2025 9:00-5:00 Central Chicago, IL

Seven things to keep in mind all the time! A tall order for a novice :(

This is a great list. Keeping.