The List Story:

Creating Narrative through Objects

Ah, the list story. We, as a people, love making lists, love breaking things down into smaller chunks, into categories, into things we can say we've accomplished or gathered. A general accounting of things, feelings, dreams, and goals is satisfying to whatever itch arises in our brain. A story is another way of organizing and structuring our thoughts, experiences, hopes, and fears; therefore, it seems natural to combine lists with narrative. However, the problem arises when the list itself fails to provide us with the window, mind, or motivation of a character, when the words are merely words and lack any further connotations or deeper meaning. If characters are often revealed through their actions, then how do we make something static, like a list, come alive and immerse us in the experience of a character's life or moment? That is the risk and the challenge of using this format to create a satisfying story. And in like a lot of the pieces we’ve looked at in this club, that is a question each reader will have to ask themselves: is this a story? Is it satisfying? Does it have a sense of stakes and tension that lights up my brain? Do I care?

We’ll start by examining “Act As If” by Miriam Gershow, as it employs a traditional flash word count.

Of the two stories, the first uses an opening paragraph before the list, as the title doesn’t provide insight into the story structure, unlike the second story. The opening offers a context for why the story is constructed from a list.

In the bottom of Zadie’s purse, as she sits in a lightly upholstered chair at the DMV to get her license reinstated, everyone packed in side by side by side, Zadie number 23 with number 72 currently being served:

We are provided with pertinent information, such as the name of the character, her location, the reason she is there, and why she might be waiting a while. This information serves to highlight the story's unusual formatting and the necessity of the wait. The context allows us to fill in some of the white space, as we’ve all been waiting somewhere like the DMV before. With this unwanted extra time, we might start to take stock of the items in our wallet, pocket, or purse.

A half-wrapped mint filched from the bowl on the hostess stand at the Mexican restaurant Phil drove them to last Wednesday, the mints there for the taking, but Zadie with the feeling she was stealing, Zadie always with the feeling of being caught, the unwrapped half tacky to the touch, gathering lint;

Lint from wadded up tissues for nagging allergies and occasional (if no longer frequent) crying jags;

One useless tampon still in its crinkly wrapper, hearkening a bygone era, testament to Zadie’s wont toward accumulation, everything gathering and taking permanent root;

Gershow does a great job of giving us an object to focus on from the purse, each one numbered, and each one offering some insight or a view into the mind or psyche of Zadie. There is evidence for why she has it and how having it has made her feel. These are very specific items, and they lead to specific past actions and or feelings about those actions. Gersgow, through this list, is asking the reader to use incomplete information to build a kind of pastiche of this character, and through this, we will come to know her more than we did in the beginning. She is a character who feels guilt, has been crying a lot lately, and is a collector of items and, therefore, experiences.

4. Nicorette gum 15-pack, four pieces left, 11 hollows in the plastic packaging big enough for the tip of her ring finger to fit in and out of, like playing hidden harmonica, good for keeping her hands busy;

Red chip that replaced first Zadie’s beginner’s-luck green chip, then later, her claw-her-way-back, mouth-full-of-hot-spit-day-after-day silver chip;

Auto insurance card with a quarterly premium that could buy instead a halfway decent used couch off Craigslist, three credits at the nearest community college for training in auto maintenance or graphic design, ten bottles of single barrel straight bourbon;

The flip phone she’d replaced her smartphone with, so she’d have one less thing calling out every second of every day for wanting;

Notice how specific the items are, down to the way the packaging feels in her hands, how she fiddles with it, how these chips denote a possible issue with addiction, but that she is trying to rehab as well. How she’s not content with her finances, how she could be doing something else with her money, how this shows a sense of her desires, her regrets. In the front story, she is only statically sitting and waiting, and instead of learning who she is by her outward glances toward the other customers, we get an inward look at her through the objects in her purse and the narrator’s willingness to create mini-scenes, half-started scenes from her past, weighted by the object!

13. Empty Altoids tin, cool in her fist till she warmed it, a feeling of power in warming it. There she was. She was there. Here. Here she was;

14. The number 23 tab she’d pulled from the dispenser after the Uber dropped her in front of the DMV, her thinking without thinking, My lucky number, even if Zadie had never been one to believe in such a thing—too whimsical—though 23 would be from here on out, lucky, even if she did not recognize it as such, a nameless warmth when she spotted 23 on a mile marker or in the license plate ahead of her on the back of a pickup, she misunderstanding luck as random anointment, not of her sweat, her effort, her own hourly, daily making and remaking.

And here we hit a kind of crescendo in her anxiety of waiting, the desperation coming out a bit more, as she uses the altered tin to ground herself in her current moment. Then, this new item, number 23, starts to gain a kind of power as she adds it to everything else in her purse. There is luck in this number as described in this small flashforward, how the narrator separates itself from her, to say that Zadie doesn’t understand that her living is its own hard-earned luck. I am not sure if this is an ending per se and if it’s totally satisfying but I do love the movement in this piece, this kind of building toward a possibility of understanding, but misconstruing it, and us knowing this is an incorrect understanding because of the separating of the narrator from the perspective of the character. It’s a bit cheeky, but it does bring us around to see her true nature in a way we might not have if this were told in a traditional format.

Our second story is “A Packing List for the End of the World” by Laura Chow Reeve. While not flash fiction, it does utilize the list structure to tell a segmented story, where each item has its own section, its own mini-story or scene. This structure builds character and momentum through each section, asking the reader to add up the elements to create a whole as they read.

First, notice how much work the title does to establish the story occasion. We don’t know why the world is ending, but that is enough to get this list story started.

FIRST AID KIT: When I was in elementary school in California, there were earthquake kits and drills that taught us to huddle beneath our tiny desks to protect ourselves from the falling rubble and debris—only a small sheet of wood to shield our small bodies from a crumbling ceiling and everything else that was toppling beyond it. Later, in Florida, there were hurricane kits. During a lonely year in Kansas, a tornado kit. Always preparing for a different disaster.

Notice that the narrator reflects on their past rather than the current story. They build a context for why they have this kit, and how many times they have tried to guard against a catastrophe in the past. This reveals a lot about their character immediately. List stories have a way of using backfill/backstory in the place of front story, but it has to be engaging and not just an information dump.

TENT: We have one from Target that fits us, our blow-up mattress, and Biscuit, snuggly but comfortably. It was only $29.99. A real deal. We probably can’t bring the blow-up mattress, though. It’s too heavy, and eventually we’ll run out of batteries for the pump. I’m assuming batteries are going to be hard to come by. That sucks because Ty has chronic back pain. That’s something you don’t see on The Walking Dead—herniated discs.

Here, the narrator’s voice comes through, making them that more specific and worthy of telling us this story. We also see that they have a sense of logic, that they are thinking of the troubles ahead. Being able to do this can add tension to a story, can give the writer something to play with or against further in the story!

WATER: I don’t know how many times I’ve Googled, does seltzer hydrate you the same as regular water. Results are inconclusive.

This is a very specific concern for this character, making them unique and specific in this story. Lists that can create or reveal character are more engaging than lists that stay too close to their real-world purposes! The more the character is revealed with the subtle tension of the looming disaster, hopefully, the more we sink into the story, the more we want to know! Each item adds the context of the choices they have made/are making. It should hopefully encourage us to continue reading.

BOOTS: It just seems like the most practical shoe choice. As a queer who has lived in the South, I have many pairs to choose from, though it’s tricky because my favorite pair technically belongs to Ty. We both wear a size 7. I bought them as a Christmas gift a few years back. They’ll probably want to wear them. I wonder how much longer Zappos will deliver.

This almost feels like our first turning point in the plot (if there is a plot?) because we learn something significant about this character and that TY is mentioned a second time, so we know that there are two characters in this relationship, that these items must work for both characters, that there is a relationship to be concerned with, to see what might happen to it before the list/story ends. There may even be a tension over the sharing of the items in the future.

While each item allows the narrator to reveal more about themselves and a bit about their current situation, there is a small aside toward the end that resonates with me.

I decide to put the plant in the ground the next time we stop, to insist that something I’ve loved will survive me.

The narrator makes an active choice to try to save something, to hope that something alive will remain alive even as the world ends, and her life will end, though she doesn’t explicitly state this. This feels like the central theme of the story that we can hope that something we love will survive, that some part of us, our history, will survive, but that we have to make an active choice/take action for this to happen. This is a small but major choice by this main character because, as we’ll see from the last item, the flashlight, she won’t have much agency in what happens to her in the future. And stories can end like this if the main character makes a big choice just before the ending.

One way to combat the biggest concern with list stories is to ensure that there is a sense of story or mini-scenes, where the characters still make choices, have some agency, and that the list doesn’t stay too close to its real-life purpose. Find ways to add characterization, conflict, tension, setting, and intrigue to make the form function as a narrative.

Prompt: Start with a packing list for a fantastical place. What would you need to bring? How can you write about each object in its own section/paragraph that creates a narrative and reveals the main character? If you were packing to be one of the first people on Mars, what would you bring? A land full of unicorns? A city inhabited by aliens? The objects can be either otherworldly or realistic, but you should provide context and meaning for each item.

Or, like Gershow’s story, your character is going through a purse, a backpack, or a relative’s home. What items would the main character find? How would these items reveal their character? What have they held onto? What have they lost? What desires can be shown through the listing of the objects? What backstories or context can be shown through the objects? Is there a sense of movement? Is there a sense of change? What small but major choice/action can they take, spurred by one of the objects?

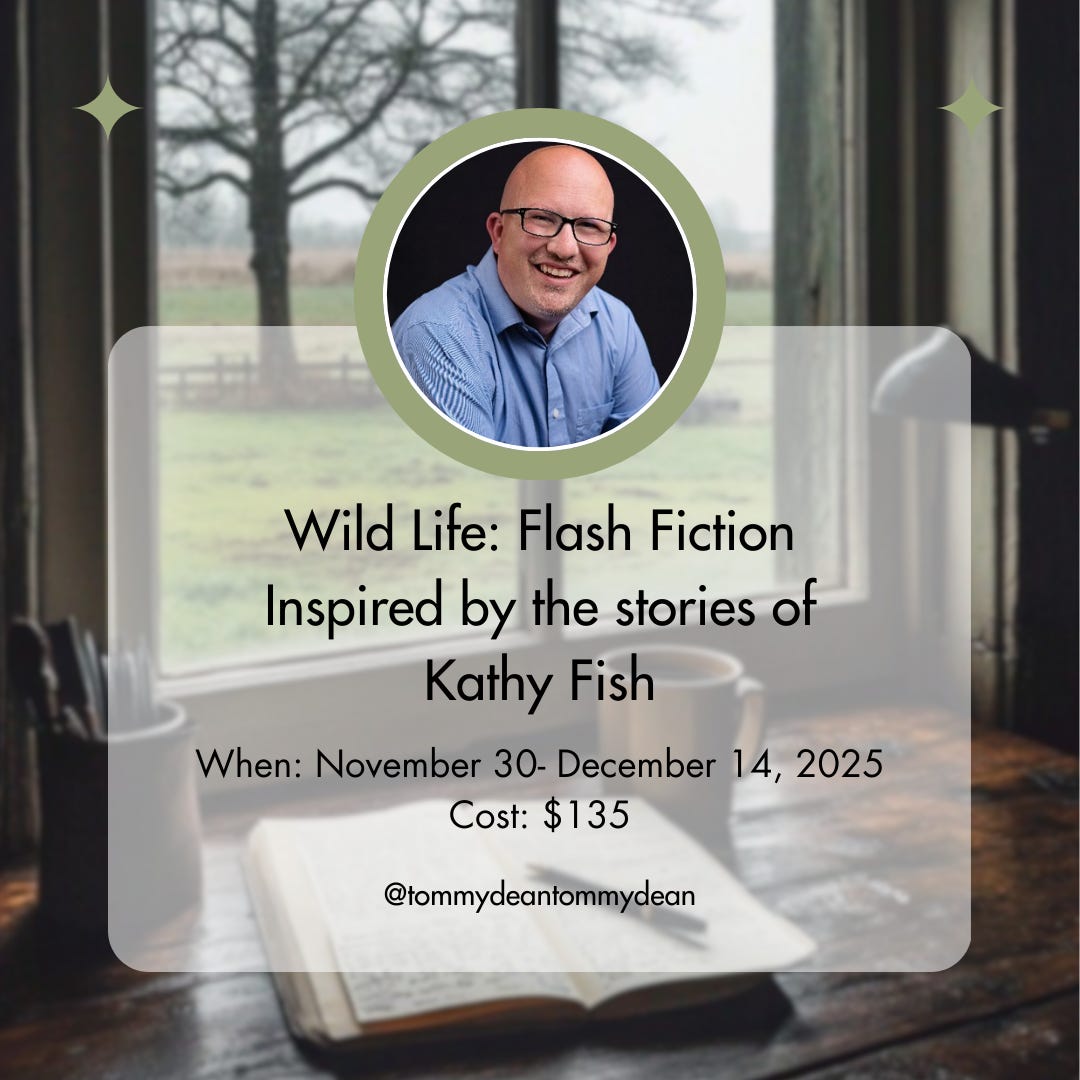

Ever feel stuck with a writing question that just won’t quit? 😩 Like, you’ve Googled, asked friends, but still no clear answer? I get it — those unanswered questions can kill your creative spark.

That’s exactly why I created the 1:1 Creative Spark Coaching Call. We’ll dive deep into your writing or publishing puzzles — whether it’s a tricky logline, writer’s block, or just where to start your novel. You bring the questions, I bring the experience as a writer, editor, and literary agent.

Ready to turn those “what ifs” into “heck yes” moments? Let’s chat and get you unstuck with confidence and fresh ideas.